Team Development

In workplace environments, teams are often confused with other subunits, including departments, divisions, or working groups. The term working group most closely resembles the meaning of teams, although there are significant differences between the two in application, if not in theory (Utley, Brown, & Benfield, 2009). Teams connote a long-term commitment, and work groups presuppose a time-limited commitment. According to Utley, Brown, & Benfield (2009), teams and work groups differ in communication methodology, decision making, motivation, participation, conflict, trust, interpersonal behaviors, and leadership. However, both teams and working groups can perform well in engineering settings. Additionally, it is possible—and it even proves to be successful, at times—to have a mixture of working group and teams—a hybrid, if you will—assigned to accomplish a particular task.

As baby boomers retire in the coming decades and are replaced by “millenials,” organizational leaders must recognize the need to build teams and systematize team operations to accommodate the needs of these younger workers. (Ferri-Reed, 2010). Of the five keys proffered by Ferri-Reed (2010), each require at least a minimum level of systemized team development:

- Start millenials on a strong footing requires mentoring, socialization, and team development experieces;

- Create a “cool” workplace that includes open workspaces, creative communications, and social networking opportunities—each of which can easily be accomplished through a strategic team structure;

- Throw them a challenge can be accomplished through team projects and special assignments;

- Reframe your coaching obviously employs a mentoring and coaching strategy; such tactics are often accomplished through team participation and development; and

- Chart a career path can require exceptional team member performance and overall team success.

In a broad implication of the power of teams and the change required to transition to teams management, one Dutch case study demonstrated that even at a national level, teams can build efficiencies between government, business and consumers (Avelino, 2009).

Team leadership plays a key role in the success of teams, and executive team leadership is discussed in the next section. But it is important to note here that the negative effect of diversity of individual values among team members can be mitigated by team leaders who are task oriented as opposed to people oriented in their management styles (Klein, Knight, Ziegert, Lim, & Saltz, 2011).

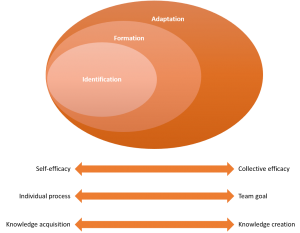

One way to build team cohesiveness, especially among millenials, is to institutionalize cross-disciplinary teams. That is, groups of individuals whose diversity of expertise, training, and experience join together to form a team focused on a particular objective. If the ultimate goal of team structure is innovation in processes, products, or services, cross-disciplinary teams are more effective than intra-disciplinary teams (Schaffer, Lei, & Paulino, 2008). This is perhaps because the innate diversity in problem solving approaches that lies within various disciplines combines with personality differences to result in ingenuity and innovation. The model presented by Schaffer, Lei, & Paulino (2008) shows how cross-disciplinary teams build upon their diversity to achieve team objectives:

As cross-disciplinary teams are identified, form, and adapt, the individual differences among team members give way to team objectives, which ultimately result in innovation, ingenuity, and new knowledge.

Teams are most successful when they exemplify seven characteristics, according to Higgs (2006). He suggests that teams and team members must embrace a common purpose, exhibit interdependence, have clarity of roles and contributions each team member makes, gain satisfaction from mutual work, shared individual and mutual accountability, realize synergies, and empowerment (Higgs, 2006).

When addressing the issue of interdependence, many managers attempt to bring about interdependence through structural means. However, a 2005 study showed that team member interdependence can be equally strong without structural means or support when group member values are egalitarian at the point of team formation (Wageman & Gordon, 2005). On the other hand, groups with members who value meritocratic values actually demonstrate low interdependency; groups with mixed personal values perform worse than those with either egalitarian or meritocratic values. Implications for managers are strong: the approach and semantics used when establishing teams and selecting team members is just as important as the skillsets of individual team members.

With the increasing global nature of business, more and more managers are adopting online or virtual teams as an affordable alternative to long-distance travel. However, virtual teams are more likely to be disengaged and lack cohesion, while face-to-face teams are able to respond more readily to feedback, develop interdependence, and achieve team objectives (Williams & Castro, 2010).

Next time, we’ll look at executive development and how critical it is to the overall health of your organization.

Sources

Antoncic, J. A., & Antoncic, B. (2011). Employee satisfaction, intrapreneurship and firm growth: a model. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 589-607.

Armstrong, P., Cockrell, B., Derrick, S., O’Leary, M., Reed, S., Sporing, J., et al. (2011). Revisiting the work-life balancing act. Public Manager, 16-19.

Avelino, F. (2009). Empowerment and the challenge of applying transition management to ongoing projects. Policy Sciences, 369-390.

Clarke, N. (2010). Emotional Intelligence abilites and their relationships with team processes. Team Performance Management, 6-32.

Clarke, N. (2010). Emotional Intelligence and its relationship to transformational leadership and key project management competencies. Project Management Journal, 5-21.

Dandira, M. (2011). Executive director’s contracts; poor performance rewarded. Business Strategy, 156-163.

Faustenhammer, A., & Gossler, M. (2011). Preparing for the next crisis: what can organizations do to prepare managers for an uncertain future? Business Strategy Series, 51-55.

Ferri-Reed, J. (2010). The keys to engaging millenials. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 31-34.

Gilad, B. (2011). Strategy without intelligence, intelligence without strategy. Business Strategy Series, 4-11.

Gumus, G., Borkowski, N., Deckard, G., & Martel, K. (2011). Healthcare managers’ perceptions of professional development and organizational support. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 42-63.

Higgs, M. (2006). What makes for top team success? A study to identify factors associated with successful performance of senior management teams. Irish Journal of Management, 161-188.

Kaufman, J. (2011). Turn apathy into engagement. Trade & Industry, 55-56.

Klein, K. J., Knight, A. P., Ziegert, J. C., Lim, B. C., & Saltz, J. L. (2011). When team members’ values differ: the moderating role of team leadership. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes.

Kong, E., & Ramia, G. (2010). A qualitative analysis of intellectual capital in social serfvice non-profit organizations: a theory-practice divide. Journal of Management and Organization, 656-676.

Lencioni, P. (1998). The Five Temptations of a CEO. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lencioni, P. (2007). The three signs of a miserable job. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Michaud, G. (2011). The freshman assessment: ensuring that your incoming executive talent quickly makes the grade. Business Strategy Series, 37.

Ricardo, H. (2010). Developing a competitive edge through employee value: how all international companies should conduct business. The Business Review, 11-17.

Schaffer, S. P., Lei, K., & Paulino, L. R. (2008). A framework for cross-disciplinary team learning and performance. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 7-22.

Street, V., Weer, C., & Shipper, F. (2011). KCI Technologies, Inc.: engineering the future, one employee at a time. Journal of Business Case Studies, 57-68.

Utley, D. R., Brown, S. E., & Benfield, M. P. (2009). Working group or team: characteristic differences. IIE Annual Conference Proceedings (pp. 415-421). New York: Norcross.

Visser, M. (2010). Relating in executive coaching: a behavioral systems approach. The Journal of Management Development, 891-901.

Wageman, R., & Gordon, F. M. (2005). As the twig is bent: how group values shape emergent task interdependence in groups. Organization Science, 687-703.

Williams, E. A., & Castro, S. L. (2010). The effects of teamwork on individual learning and perceptions of team performance: a comparison of face-to-face and online project settings. Team Performance Management, 124-147.